The significance of weight loss in the first few days after birth.

Nearly nine years ago, I was well into the second day of snuggling with my hours-old youngest son. For his birth, I had chosen the hospital in which I was employed. I hadn't done that for either of my older two sons because of insurance reasons and because I wasn't exactly sure that I wanted to blur the line between my personal and professional self for such an intimate event. But, his birth was beautiful and I was thoroughly enjoying my sweet little snuggly son. At about midnight, the (unfortunate, unlucky) nurse who was taking care of me and Ethan came in to check on us. She looked scared. She stepped (sneaked? tip toed?) maybe two feet into the room and said, "How is the breastfeeding going?" It had been great and I said as much. Her next words tumbled out in a rush. "Good, because he's down 10% from his birth weight." And whoosh, she was out the door. I do not know what I would have done in her place. I would not have wanted to tell me that news either. As I absorbed her words, I did what any other board-certified pediatrician who had earned her IBCLC would do; I burst into tears. The rational part of my brain, such as it was, would eventually win when the sun came up. Those were a long few hours.

If I asked you to lose 10% of your weight in 48 hours, how would you do it? Not eating might get you there, but not in that short of a time span. How about terrible dehydration from food poisoning with really awful vomiting and diarrhea? Maybe 48 hours of continual exercise? Or exercising while pooping and puking? Right. The suggestions are absurd. But newborn infants often do lose 10% of their weight in the first few days after they are born. What factors are contributing to that weight loss?

First, we should understand that 10% or 7% (or whatever the worry threshold is where you are) is just a number. I have mentioned that I get very frustrated when I hear numbers given out of context, especially when we act on numbers just because they are numbers. When we look for signs of health and well-being in a newborn, we gather all sorts of pieces of information that collectively give us a picture of that baby. That context helps us interpret numbers. Newborn weight loss needs a context to be meaningful. The concept that numbers need to contribute something to the care of the infant in a meaningful way is the theme behind my three B's: bilirubin, birth weight and blood sugar.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that healthy, term infants who have a weight loss of 7% from birth, should have their feeding assessed and that providers should "consider more frequent follow-up." Hopefully, we are looking at the feeding of any newborn and frequent follow up is standard of care where you are and the AAP's suggestion is reinforcing best practices. If not, you have an opportunity to change the world.

That 7% value seems to be a standard trigger for increased attention to a baby's feeding. And unfortunately, 10% weight loss seems to be the trigger for supplementation. But excessive weight loss, typically defined as weight loss greater than or equal to 10% of birth weight, is actually pretty common. Losing 10% of birth weight is common? Yes, and 7% is likely a normal, average weight loss.

In a study by Chantry et al, the authors found that 19% of exclusively breastfed infants experienced excessive weight loss in the first 3 days of life, but by day 7 most babies had regained that weight. They also determined, in what we will see is a common theme, that intrapartum IV fluids were an independent risk factor for excessive weight loss. An independent risk factor is one that can cause the outcome regardless of other factors, so, in this study, intrapartum IV fluid could cause newborn weight loss all by itself.

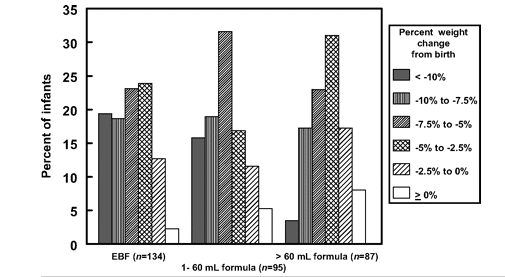

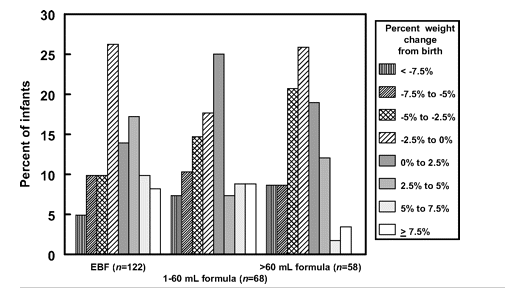

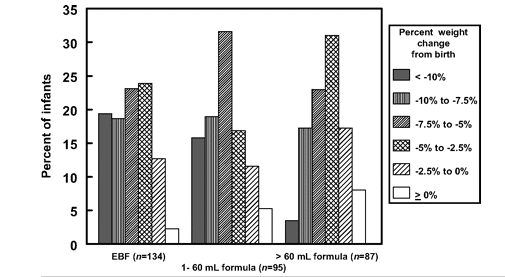

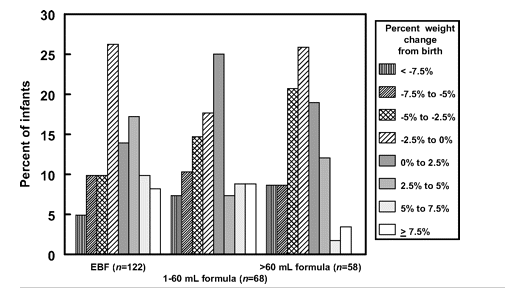

From the study: Distribution of weight changes from birth to day 7 of life according to formula supplementation category on day 3 (on left) and day 7 (on right).

By day 3, 19% of exclusively breastfed babies lost 10% or more of their birth weight.

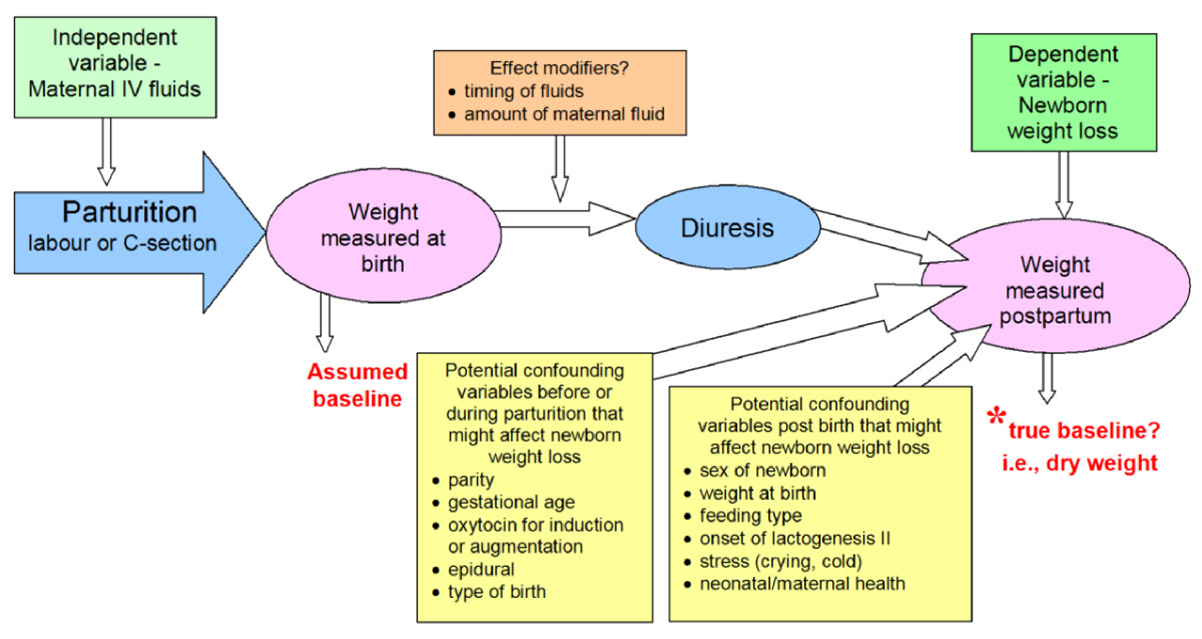

Another study, by Noel-Weiss et al, also found that intrapartum fluids are a risk factor for excessive weight loss. "Timing and amounts of maternal IV fluids appear correlated to neonatal output and newborn weight loss. Neonates appear to experience diuresis and correct their fluid status in the first 24 hours. " The authors suggest a (pretty cool) conceptual framework:

Conceptual framework includes potential confounding variables and effect modifiers. Noel-Weiss et al. International Breastfeeding Journal 2011 6:9 doi:10.1186/1746-4358-6-9

In a study done in rural Zaire, the average weight loss after delivery was 7%. Another study done in Italy found that weight loss of 10% was common in the first few days of life, especially after C-sections.

So, lots of exclusively breastfed kids lose weight and at least one reason to explain that weight loss is that they are peeing off fluids given to their mothers while they were being born. That just makes sense. And makes a whole lot more sense than they are exercising or suffering from food poisoning. I might be making a case here for not worrying about weight loss in the neonatal period at all. But we can not be that cavalier.

Weight loss is important because some kids who lose weight need no intervention at all. Some weight loss is preventable. And some weight loss is real and scary. The key is knowing which babies are in trouble and then having access to somebody with the skill set to know which weight loss is significant and needs intervention.

One way to assess adequate transfer of breastmilk is to monitor stool output. Urine output is usually a good way to monitor fluid intake, but if our baby is going to be peeing off lots of fluid from birth interventions, urine output may be great. In fact, the urine output might be awesome. But, in the first few days after birth, the urine output maybe artificially good as the baby becomes less of a water balloon. So, what did not get messed up by delivery? Poop.

Colostrum is full of oligosaccharides: prebiotic, non-digestible sugars that play a crucial role in the development of the neonatal immune system. Since oligosaccharides are abundant in milk and are non-digestible, the more the baby gets, the more poop there is. The more milk the baby gets, the more stool output. we can use stool output as a good marker of the adequacy of breastfeeding. We would like to see the baby clear all the meconium by 4-5 days of life (maybe a day later for babies born via C-section).

Weight can also be influenced by which scale we use, under what conditions the baby is weighed (dressed, naked?), and whether the have just eaten, peed or pooped (every ounce counts!) We can also look at the trend in weight loss over time. If a baby has lost 10% in 72 hours, what was the pattern of the weight loss? If the baby experienced a normal fluid diuresis, the weight loss pattern may have been 8% in the first 36 hours and only 2 % since.

Neonatal weight loss can therefore be interpreted in a context which looks, not just at the number, but at the baby, the stool output, the conditions of mom's labor, and the feeding. Understanding the many variables that can influence weight loss helps us decide which baby needs intervention and which babies do not. However, too often we are not putting weight loss into context. Kids are getting supplemented just because of a number. Just one bottle of formula can make a huge difference in how that baby's immune system develops. We should have a very good reason for supplementing. But do we?

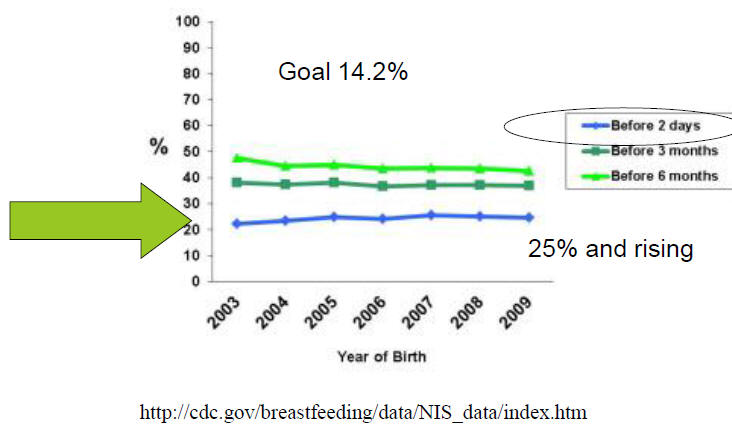

Check out the graph from the CDC, specifically the blue line. According to this graph, more than 20% of kids in the US are being supplemented with formula before 2 days. That makes no sense. Surely, our species can do better than having one in five newborns needing supplementation to survive the first 2 days of life.

Since we know that weight loss after birth is influenced by many factors, we could share that information with the mother. Empowering the mother and her support system with knowledge about what is normal and expected is crucial. And may even prevent her from crying and feeling like a failure at midnight.

Jenny Thomas, MD, MPH, IBCLC, FAAP, FABM (and Ethan)

Follow Me: LMC Breastfeeding